Endorsed by the Environment and Invasives Committee 2024. Information is current as of the time of writing (2012).

DOWNLOAD AS PRINTABLE PDF

Background

Dogs are used for a range of pest animal control operations. This procedure provides advice on first aid and basic care for dogs used in these situations. It is written to prevent harm to dogs and encourage their humane treatment.

This National Standard Operating Procedure (NATSOP) is a guide only; it does not replace or override the legislation that applies in the relevant state or territory jurisdiction. The NATSOP should only be used subject to the applicable legal requirements (including OH&S) operating in the relevant jurisdiction.

Application

- This document is a guide for people using dogs for certain aspects of pest animal control. For example:

- Mustering of feral goats

- Flushing feral pigs and foxes out of vegetation prior to shooting

- Driving the last remaining rabbits underground prior to warren fumigation or destruction

- Protecting herd animals with guard dogs.

- When performing these procedures the welfare of the dogs may sometimes be at risk. All reasonable steps must be taken to safeguard the dogs from injury or distress, and appropriate training of dogs and their handlers is essential.

- A first aid kit should be carried at all times when there is a risk of injury (see Table below).

- If dogs are injured when performing pest animal control procedures, they should receive prompt first aid and veterinary treatment if required.

- All diligent care should be taken by owners and handlers for the safety of dogs involved in pest animal control operations.

| Important phone numbers |

Equipment and supplies |

Bandaging materials |

Medicines and other

|

Veterinary clinic phone number and directions to the clinic

Poisons Information Centre ph 13 11 26 |

Spare collar and nylon leash

Muzzle or roll of gauze for making a muzzle

Scissors

Tweezers

Small flashlight or penlight

Towel or blanket to use a as stretcher and another to keep the dog warm

Splint – e.g. pieces of wood, aluminium rods (stiff but bendable) the same length as the dog’s leg

2 pairs of thick socks to fit dog’s paws loosely, and adhesive tape to attach

Latex gloves |

Gauze sponges of various sizes, some sterile

Roll gauze, 5 cm width

Non-stick sterile pads

Bandages – crepe, vetwrap cohesive

Adhesive tape – e.g. elastoplast |

Electrolyte solution such as Lectade®, plus water for reconstitution

Emetic – e.g. washing soda crystals, dilute hydrogen peroxide solution (3% solution) plus dosing syringe

Eye wash solution- sterile water or saline

Antiseptic solution – e.g. Betadine®

Container of cool, fresh water for drinking, cleaning and cold compresses |

Injuries and first aid

- The most common and/or important injuries which occur to dogs used in pest animal control include: lacerations; haemorrhage; bone fractures; dehydration; snake bites; poisoning; eye injuries; burns; hyperthermia and hypothermia.

- Injured dogs may suffer shock.

- The most extensive or severe injuries may necessitate emergency euthanasia.

- Otherwise if there are injuries such that movement and handling appear to be painful, a veterinarian must be consulted. Handlers should take care to avoid being bitten; dogs that are in pain or distress can bite in self-defence. Always muzzle an injured dog before handling or moving it, unless it is unconscious, has difficulty breathing, is vomiting or has a mouth injury.

Emergency procedures

Lacerations

- Small cuts which stop bleeding within a few minutes will generally require little attention other than to keep them clean. Depending on the size and the degree of wound contamination, suturing and/or the use of antibiotics may be appropriate. These should be carried out by a veterinarian, but would not require immediate attention.

Haemorrhage

- Larger wounds or those which involve major blood vessels may continue to bleed profusely. This blood loss may be life threatening and should be stemmed by the application of direct pressure to the wound using swabs / towels / bandages or similar. The dog should be presented for veterinary attention immediately. Severe blood loss will result in haemorrhagic shock, where vital organs are starved of blood supply and death results. A tourniquet may be used where haemorrhage from a limb cannot be controlled by direct pressure. The tourniquet must be tied between the top of the leg and the wound and loosened for 20 seconds every 15 minutes. A tourniquet is dangerous and should only be used in life-threatening haemorrhage of a limb. It may result in amputation or disability of the limb.

- Haemorrhage may also occur internally into the abdomen or chest, where the lost blood cannot be seen. This may occur after blunt injuries such as being hit by a car or trampled by a large animal. The bleeding may not be apparent until signs of shock develop (see below). In some cases, bleeding may be seen from the nose, mouth, rectum, in urine or coughed up. The extent of internal bleeding is difficult to assess and so these animals require immediate veterinary attention.

Shock

- Loss of large amounts of blood will result in vital organs obtaining insufficient blood to function. This is an emergency which requires immediate veterinary attention. Signs of shock include: collapse, weak or rapid pulse, shallow rapid breathing, disoriented appearance, pale-almost white-mucous membranes (e.g. gums and conjunctiva).

- The dog should be kept quiet and warm. If possible, keep the head at or below the level of the rest of the body.

Dehydration

- Long periods without sufficient water, especially in hot weather, or protracted vomiting/diarrhoea can cause the dog to become dehydrated. A sign of dehydration is that the skin on the back of the neck, when pulled up, does not spring back to its normal position within about a second. Severe dehydration may also result in shock (see above).

- Treatment involves administration of fluids by a veterinarian. In the interim, if the dog is not vomiting, fluids such as water or Lectade® (an electrolyte solution available from a vet) can be given by mouth in frequent small doses.

Snake bites

- Bites from many Australian species of snake can kill a dog within minutes if sufficient venom is injected. Signs of snake bite include swelling and bruising around the bite; vomiting; paralysis of hind limbs, progressing to the entire body and; nervous signs such as twitching and drooling. Signs of shock may become apparent.

- If snake bite is suspected:

- Attempt to identify the snake, but do not get bitten! Do not attempt to kill the snake for the purposes of identification.

- If the bite can be seen on a limb, bandage the whole limb firmly but not tightly. This may slow the spread of the venom from the bite site.

Do not wash the bite site. Venom at the site may be used to identify the type of snake.

- Attempt to keep the dog calm and still. If possible carry the dog to the car (as any movement may cause the toxin to spread faster) and seek immediate veterinary attention.

Tick paralysis

- Found in coastal areas of Eastern Australia, particularly in bushland, the paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus, injects a toxin when attached to feed on the blood of dogs, cats and other animals. This toxin causes a neuromuscular paralysis which usually begins in the hindlimbs and progresses to affect the forelimbs and muscles of breathing and swallowing. Dogs usually die from respiratory arrest or complications such as pneumonia. Signs usually start with an unsteady hindlimb gait, progressing to a reluctance or inability to walk, change in bark, cough, vomiting or regurgitation and laboured breathing. The time from tick attachment to the appearance of clinical signs can range from less than 24 hours to a week or more, but generally takes a couple of days. On short trips, signs often appear only once the dog has returned home, but on longer expeditions, they may appear while still in the field.

- First aid treatment is limited. The dog should be repeatedly checked all over for ticks, which should be removed, with the mouth parts if possible, and saved for identification. If signs appear, the dog should be kept calm in a cool environment and not offered food or water (except in high temperatures or humidity and only if the dog is still able to swallow normally), and presented for immediate veterinary attention. The chance of recovery is highest for those dogs treated when the signs are still mild.

- Try to prevent tick paralysis by closely examining the dog for ticks at least once daily, including between the toes, in the ears and mouth and under the tail, and removing any ticks. Application of a ‘spot-on’ or spray product licensed for the control of paralysis ticks in dogs at the recommended intervals will decrease the risk of tick paralysis but daily inspections should still be carried out.

Poisoning

- The symptoms and treatment of poisoning depend on the nature of the poison. For instance, dogs poisoned with 1080 should be made to vomit if not yet showing signs of toxicity, whilst vomiting should not be induced when an animal has ingested a corrosive or caustic substance. Some poisonings may be treated with specific antidotes whilst others can only be helped by providing supportive treatment. Standard Operating Procedures for the control of pest animals which involve a risk of poisoning give more specific advice on each poison. However, the dog should be presented to a veterinarian for assessment and treatment.

Hyperthermia (heat stroke)

- Long periods of exercise in high temperatures, especially with limited access to water, or a period inside a car even in relatively mild temperatures, can cause failure of the dog’s cooling system and the body temperature can rise to levels which threaten life. Signs include excessive panting, collapse, increased heart and breathing rates, salivation, reddened mucous membranes and convulsions or coma. The body temperature should be measured using a rectal thermometer and may exceed 43ºC.

- The dog should be taken away from the source of heat and cooled by the use of running cold water, electrical fans or cold water soaked sheets. This should be continued until the body temperature falls to 40ºC, then discontinued. Even after cooling, serious complications can develop and the dog should be given veterinary attention.

Hypothermia (low body temperature)

- Dogs exposed to cold, wet, windy weather, especially if old, injured or undernourished, can lose their ability to maintain their body temperature. Hypothermia may be defined as a body temperature of 35ºC or below. If body temperature falls to 25ºC or below, it is unlikely that the dog will survive.

Hypothermic dogs feel cold to touch, have a decreased heart rate, weak pulse and pale mucous membranes. They may be shivering or semi/unconscious.

- They should be placed somewhere warm, wrapped in a blanket and have a hot water bottle wrapped in a towel placed on or under them. Do not try to raise the dog’s temperature too quickly. Supply these first aid measures and seek immediate veterinary attention. Body temperature must only be raised slowly over a period of hours. Even then, potentially fatal consequences may still occur.

- Note that dehydration commonly occurs with both hyper- and hypothermia and this should be addressed.

Eye injuries

- Common eye injuries include penetrating wounds (e.g. from branches) and foreign bodies in the eye. In both cases the dog is likely to paw or scratch at the eye making the condition worse. If a foreign body (e.g. grass seed) is suspected, the eye should be held open and flushed with sterile saline or water. An Elizabethan collar can be attached to the dogs collar to prevent it from scratching at the eye and causing further damage. Undislodged foreign bodies or ulceration of the eyeball will require veterinary attention. Penetrating injuries to the eyeball will require immediate veterinary attention.

Fractures

- Commonly fractures occur as a result of trauma and areas most often affected are the legs and pelvis. All fractures require veterinary attention. However, the case is more urgent where it is accompanied by profuse bleeding or signs of shock.

- Signs of fracture include lameness, pain, inability to use one or more limbs and changes to the shape of limbs. An open fracture may show bone ends protruding through a wound in the skin. If a fracture is suspected:

- Gently lay animal on a board, wooden door, tarp, etc. padded with blankets.

- Secure the animal to the support.

- Do not attempt to set the fracture.

- If a limb is broken, wrap the leg in cotton padding, then wrap with a magazine, rolled newspaper, towel or two sticks. Splint should extend one joint above the fracture and one joint below. Secure with tape. Make sure wrap does not constrict blood flow.

- If the spine, ribs, hip, etc. appear injured or broken, gently place the animal on the stretcher and immobilise it if possible.

Burns

- Burns may occur from contact with chemicals or fire/hot surfaces. Severe (deep and/or extensive) burns will result in loss of body fluids and may result in dehydration and shock and require immediate veterinary attention.

- The affected skin should be flushed with cold water for at least ten minutes. The burn should then be covered with a clean non-stick dressing and the dog presented for veterinary attention.

Euthanasia

- Euthanasia of dogs should be carried out by a veterinarian. If this is not possible, a gunshot to the head may be the next best option. This should be undertaken only by a fully competent, licensed person, taking special care to safeguard people and other animals in the area. The welfare of the dog being shot must be given prime consideration.

- Smaller calibre rifles such as a .22 rimfire or .22 magnum rimfire with hollow/soft point ammunition are recommended for euthanasia at close range (<5 m).

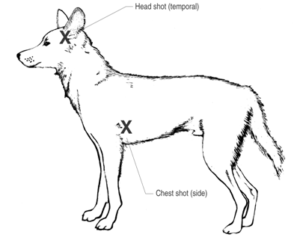

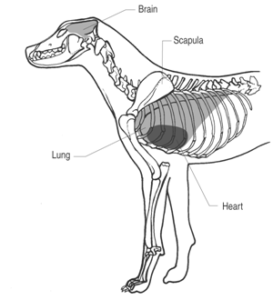

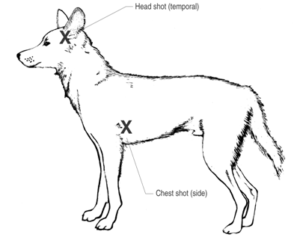

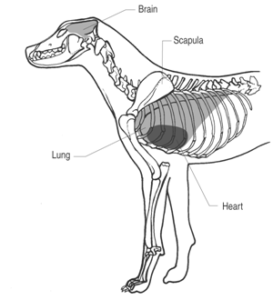

- Shots must be aimed to destroy the major centres at the back of the brain near the spinal cord. This can be achieved by one of the following methods (see Diagrams 1, 2 and 3):

Frontal position (front view)

- The firearm is aimed at a point midway between the level of the eyes and the base of the ears, but slightly off to one side so as to miss the bony ridge that runs down the middle of the skull. The aim should be slightly across the centreline of the skull and towards the spine.

Temporal position (side view)

- The firearm is aimed horizontally at the side of the head at a point midway between the eye and the base of the ear.

- Death of shot animals should always be confirmed by observing the following:

- absence of rhythmic, respiratory movements

- absence of eye protection reflexes (corneal and palpebral reflexes or ‘blink’)

- a fixed, glazed expression in the eyes

- loss of colour in mucous membranes (become mottled and pale without refill after pressure is applied).

- If death cannot be verified, a second shot to the head should be taken immediately.

Use of muzzles and other protective equipment

- Muzzles are often used to prevent bite injuries when handling feral livestock animals. They are also used to prevent injured dogs from biting handlers and to prevent dogs from eating poison baits.

- A muzzle is usually made of leather, nylon, wire or plastic and it fits over the dog’s nose and mouth in such a way that the dog is prevented from biting or eating. Some open wire muzzles are large enough to allow the dog to open its mouth to pant and drink water. The wire (or cage) muzzle should be used when the weather is hot.

- Muzzles should fit comfortably without chafing the skin or impeding breathing. They should not be left on dogs which are unattended.

- Muzzles which prevent the dog from panting or drinking must not be used if the dog is likely to become hot or thirsty or if the muzzle is to be left on for more than a few hours.

- Dogs may initially find the wearing of a muzzle frightening or distressing. There should be a period of preconditioning with supervision by the handler.

- Coats or rugs may be required to protect dogs from cold, inclement weather, especially young and old dogs.

- When using dogs to flush out feral pigs, chest, neck and body plates should be used to help prevent serious injuries.

Identification of dogs

- Dogs, by law, must wear a collar and up-to-date identification at all times. Collars should not be too restrictive or too loose.

- Registration tags must also be attached as required by local or state/territory legislation.

- All dog owners are encouraged to have their dogs’ microchipped by a veterinarian, or another appropriately qualified person. This additional method of identification can be read by veterinarians, animal welfare shelters or council pounds if the dog’s collar has been lost or removed. For the protection of your animal, it is preferable that the microchip system offers a life-of-pet registration and has a national register accessible 24 hours a day.

- In some situations (e.g. when using dogs to flush out feral pigs) it is recommended that dogs wear a working radio collar or GPS collar so that they can be quickly located if lost. Lost dogs can suffer from dehydration, starvation and exposure. They can also become feral, join other wild dogs and have a serious negative impact on livestock and native fauna if they are left to run wild.

Basic care of dogs

The following information is extracted from the NSW DPI publication Animal Welfare Code of Practice: The Care and Management of Farm (Working) Dogs (2004). The Code recommends minimum standards that ensure the health and well-being of working dogs.

The basic needs of dogs are:

- Accommodation that provides protection from the elements

- Freedom of movement

- Readily accessible water and appropriate food

- Timely recognition and treatment of disease and injury

- A safe transportation system to and from places of work

- Adequate exercise.

Responsibilities of the owner

The owner of working dogs is responsible for:

- Providing accommodation and equipment suitable for the size

- Providing adequate protection from adverse environmental conditions and climatic extremes

- Providing sufficient space for dogs to stand and move freely at all times, including any periods of transportation

- Providing appropriate food and water to maintain good health

- Reasonable protection from disease, distress and injury

- Providing prompt veterinary treatment in the case of injury or illness

- Maintaining hygiene in the premises where dogs are kept

- Supervising regular feeding and watering

Housing of dogs

Kennels

- Kennels should be provided to protect dogs from adverse weather.

- Kennels should be situated so that a chained dog can reach the kennel and the water supply.

- Kennels should have adequate ventilation.

- Kennels made from metal should be situated out of direct sunlight or should be effectively insulated.

- Chains used to restrain dogs near a kennel should have a swivel set between the chain and the securing clip. The swivel should be maintained in proper working order.

Pens

- Pens should be provided to protect dogs from adverse weather.

- Pens should provide enough space for each dog to sit, stand, sleep, stretch, move about and lie with limbs extended.

- The pen must be of sufficient size to allow the dog to urinate and defecate in an area well away from feeding and bedding areas. Alternatively, pens may be raised above the ground with a slatted area for urination and defecation.

- Pens should provide adequate protection from weather through the provision of a kennel or other shelter.

- Pens and kennels should be well ventilated to maintain an environment free of dampness and noxious odours but without draughts.

Pens should be drained appropriately to allow water to run off.

- Faecal or urine contamination of earth in dirt pens should be avoided. The surface of the pen should be sealed or gravelled if it becomes muddy.

- A separate pen should be used for any whelping bitches.

Running chains

- Running chains should be designed in a way that prevents entanglement. Dogs should be able to reach shelter and water without the dropper chain becoming entangled in any obstruction along the running line or its attachment points.

- The chain, swivels and running line should be regularly checked for signs of wear.

- The running line should be of sufficient length to allow reasonable exercise.

- The dropper chain should be of sufficient length to allow reasonable sideways movement and must incorporate a swivel between the clip and the chain.

Hygiene

- Pens should be kept clean for the comfort of dogs and for disease control. Faeces should be removed regularly.

- Every effort should be made to control pests including fleas, ticks, flies, lice and mosquitoes.

- Dogs should only be treated with chemicals registered for dogs and only in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Health care

- Dogs should be regularly vaccinated against distemper, hepatitis and parvovirus.

- A program for the control of internal and external parasites should be established in accordance with veterinary advice.

- Health and welfare should be routinely checked in the daily management of working dogs. This should include observing whether a dog is eating, drinking, urinating, defecating and behaving normally.

- Veterinary attention should be sought if a dog shows any signs of ill health.

Diet

- Dogs should receive appropriate, uncontaminated and nutritionally adequate food and water. The food must be in sufficient quantity and of appropriate composition to provide for:

- The normal growth of immature dogs.

- The maintenance of reasonable body condition in adult working dogs.

- The requirements of pregnancy and lactation in breeding bitches.

- Feeding of uncooked offal should be avoided to prevent the spread of tapeworm and hydatids.

Exercise

- Dogs should have the opportunity for regular exercise:

- To allow them to urinate and defecate

- To give them contact with humans and other dogs

- To allow them to be observed for any problems

- To let them stretch their limbs.

- Dogs that are not working should receive sufficient exercise to maintain their health and fitness. Ideally, all confined dogs should be given at least 30 minutes off the chain or out of their pen each day.

- Active or old dogs may require more or less exercise than specified.

Transport

- Any vehicle regularly used for transporting dogs should:

- Protect dogs from injury

- Have non-slip floors

- Protect dogs from exhaust fumes and extremes of temperature including hot metal floors

Kept clean.

- Water should be provided during transportation.

- Muzzling of some dogs may be required for their own protection or that of other dogs.

- Dogs restrained on the back of a moving vehicle should be kept on a sufficiently short lead to prevent movement beyond confines of the vehicle. Hanging over the side of vehicles must be prevented.

References

- van Bommel L (2010) Guardian dogs: best practice manual for the use of livestock guardian dogs. Invasive Animals CRC, Canberra.

- King J (Ed.) (1999). Pet First Aid for Cats and Dogs. Australian Red Cross and RSPCA. Impact Printing, Australia.

- Ministry for Primary Industries (2010). Animal welfare (Dogs) Code of Welfare. Animal Welfare Advisory Committee, Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ.

- NSW DPI (2004). Animal welfare code of practice: The care and management of farm (working) dogs. NSW DPI, Orange, NSW.

Invasive Animals Ltd has taken care to validate the accuracy of the information at the date of publication [April 2013]. This information has been prepared with care but it is provided “as is”, without warranty of any kind, to the extent permitted by law.