Endorsed by the Environment and Invasives Committee 30 August 2024.

DOWNLOAD AS PRINTABLE PDF

Background

Aerial shooting of feral pigs from a helicopter is used in extensive or otherwise inaccessible areas. It is an effective and relatively cost-effective method of quickly reducing feral pig populations. Teams involved in shooting from a helicopter require (at minimum) a shooter, and the pilot. The inclusion of an observer or navigator can also be incorporated into the shooting team. The pilot aligns the helicopter for the optimum shot, advises the shooter when to shoot and can also confirm death and advise on requirements of additional shots for humaneness purposes.

Aerial shooting is a humane method of killing feral pigs when it is carried out by appropriately accredited, experienced and skilled shooters and pilots; the animal can be clearly seen and is within range; the correct firearm, ammunition and shot placement is used; and wounded animals are promptly located and killed.

This National Standard Operating Procedure (NATSOP) is a guide only; it does not replace or override the relevant state or territory legislation. The NATSOP should only be used subject to the applicable legal requirements (including WHS) operating in the relevant jurisdiction.

Individual NATSOPs should be read in conjunction with the overarching Code of Practice for feral pig. This is to help ensure that the most appropriate control techniques are selected and that they are deployed in a strategic way, usually in combination with other control techniques, to achieve rapid and sustained reduction of feral pig populations and impacts.

Application

- All aerial shooting programs in accordance with relevant state, territory and federal legislation.

- Shooting of feral pigs should only be performed by competent, trained personnel who have been tested and accredited for suitability to the task and marksmanship and hold the appropriate licences and accreditation.

- Aerial shooting should only be used in a strategic manner as part of a coordinated program designed to achieve sustained and effective control.Aerial shooting is a cost-effective method where pig density is high or the area is inaccessible. Costs per pig increases as pig density Also, pigs learn to avoid helicopters, so successive shoots can become less effective.

- Aerial shooting is best suited to areas where pigs are living and feeding in extensive or inaccessible areas (e.g., swamps, marshes and rough terrain or broadacre crops) where vehicle access is impossible or impractical and/or pre-feeding will not successfully attract enough pigs for trapping or baiting.

- There are two scenarios in which aerial shooting can be used. The first in areas of closed vegetation (e.g., heavily vegetated creek lines, woodlands and dense forest), effectiveness is limited since pigs may be concealed and difficult to locate from the air. In this scenario aerial shooting would be a supplementary method. The second scenario is in relatively open country where pigs are highly visible and readily shot. Aerial shooting here would be a primary method of control.

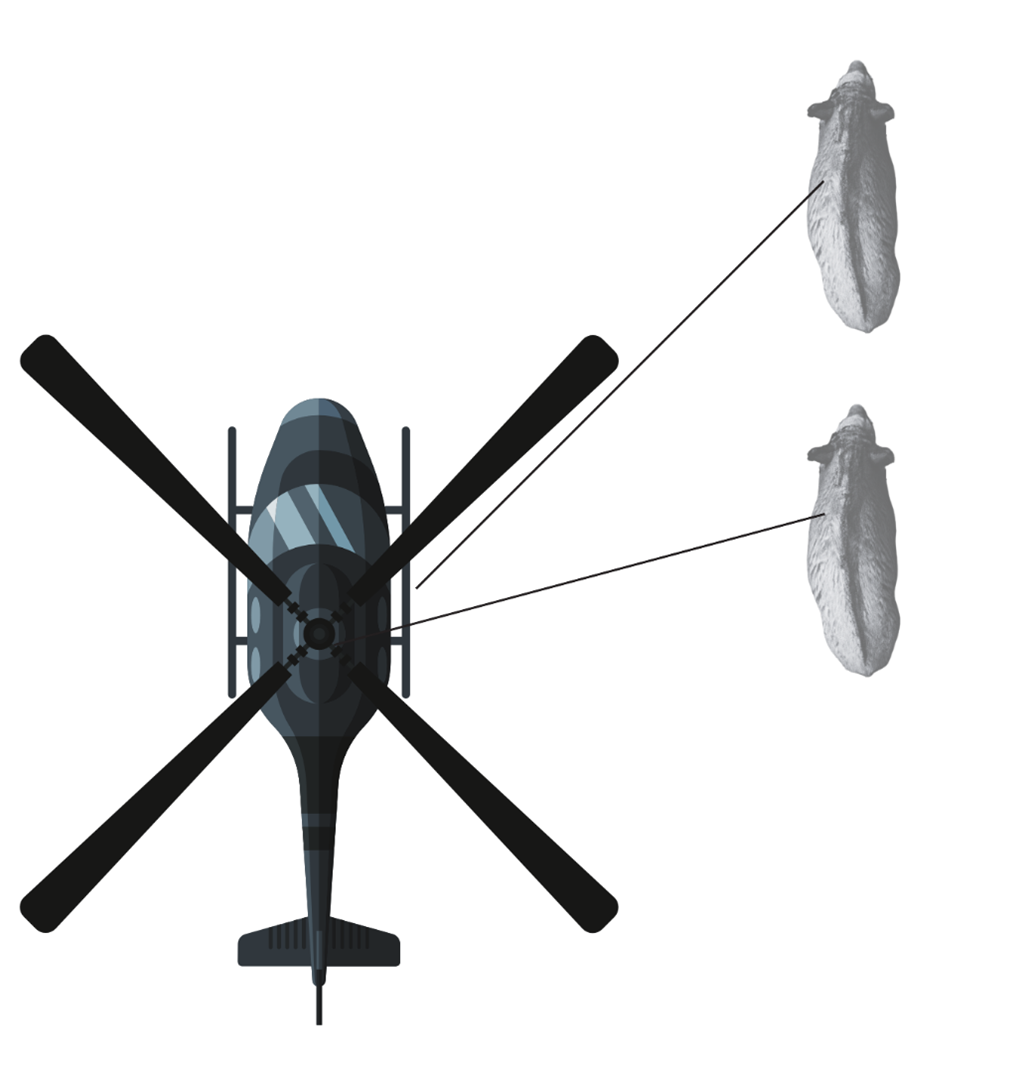

- Thermal assisted aerial culling (TAAC) is a new aerial shooting technique used in some states and territories. This technique usually incorporates a dedicated thermal camera operator (or thermographer) into the aerial shooting crew to search for and identify target animals. Where environmental conditions are suitable, TAAC can improve the efficacy and efficiency of aerial shooting programs aiming to remove low-density feral pig populations from the landscape, particularly in heavy vegetation, to achieve localised eradication. The optimal period for aerial shooting is when pigs are away from cover g., during dry seasons or droughts when pigs are forced to congregate in areas with limited access to water and feed.

- In addition to dedicated TAAC operations, conventional aerial shooting programs can be enhanced by using thermal imaging equipment (e.g. thermal binoculars or monocular), when environmental conditions are suitable.

- Operators (including helicopters, pilots, shooters and navigators/observers) must hold the appropriate licences and permits and be skilled and experienced in aerial shooting operations.

- Helicopter operators must have approval from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority to undertake aerial shooting operations.

- Aerial shooting must comply with all relevant federal and state legislation, policy and guidelines.

- Storage use and transportation of firearms and ammunition must comply with relevant legislative requirements.

Animal welfare implications

Target animals

- The humaneness of aerial shooting as a control technique depends on the skill and judgement of both the shooter and the pilot. If properly done, it can be a humane method of killing feral pigs.

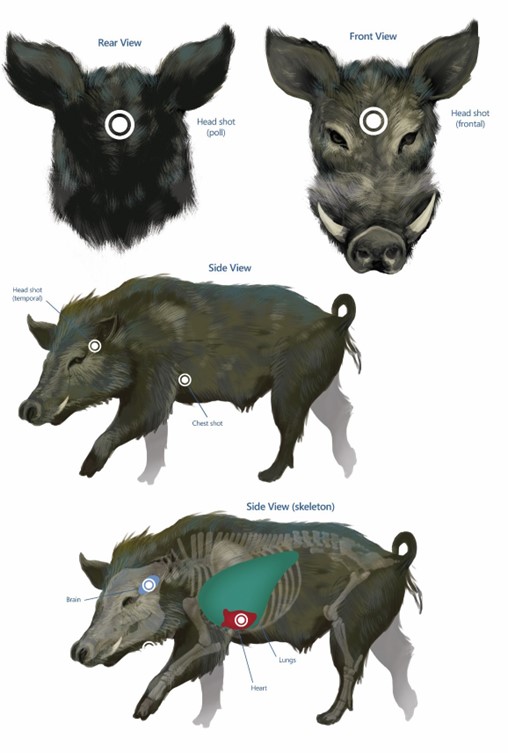

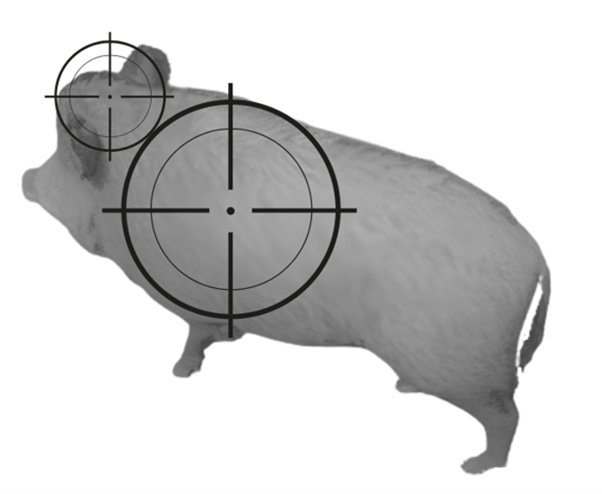

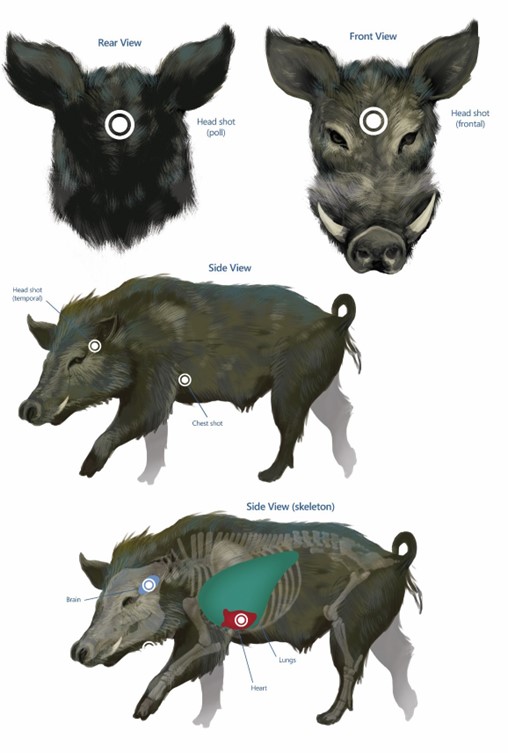

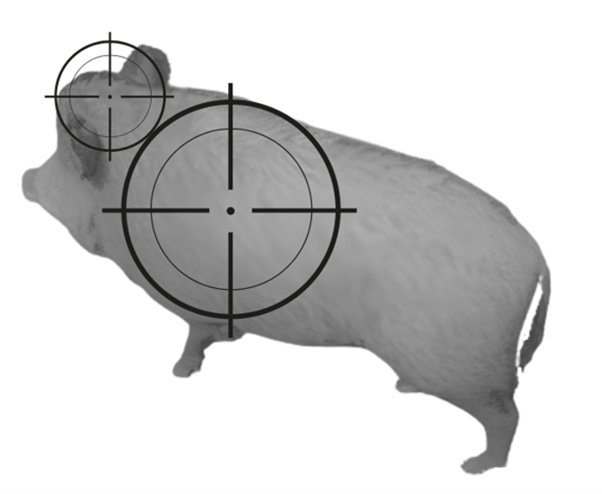

- Only chest (heart-lung) or head (brain) shots must be used (Figure 1). Although well-placed head shots result in instant insensibility, a more realistic target point for aerial shooting of feral pigs is the larger heart-lung zone (Figure 2). The initial head shot must be followed up with a further accurate heart-lung shot once the animal has The only exemption to two shots is when the heart/lung is completely destroyed as may be the case with smaller animals. This deliberate ‘overkill’ policy is aimed at ensuring a quick death given the difficulty in confirming death from the air.

- Death from a shot to the chest is due to massive tissue damage and haemorrhage from major blood Insensibility will occur sometime after the shot, ranging from a few seconds to a minute or more. If a shot stops the heart functioning, the animal will lose consciousness very rapidly. Correctly placed head shots cause brain function to cease, and insensibility will be immediate.

- Shooting must be conducted in a manner that maximises its effect to cause rapid death. This requires the use of appropriate firearms and ammunition.

- A target animal should only be shot when:

- it is clearly visible and recognised

- it is within effective range of shooter and the firearm and ammunition being used

- a humane kill is highly

- if in doubt do NOT shoot.

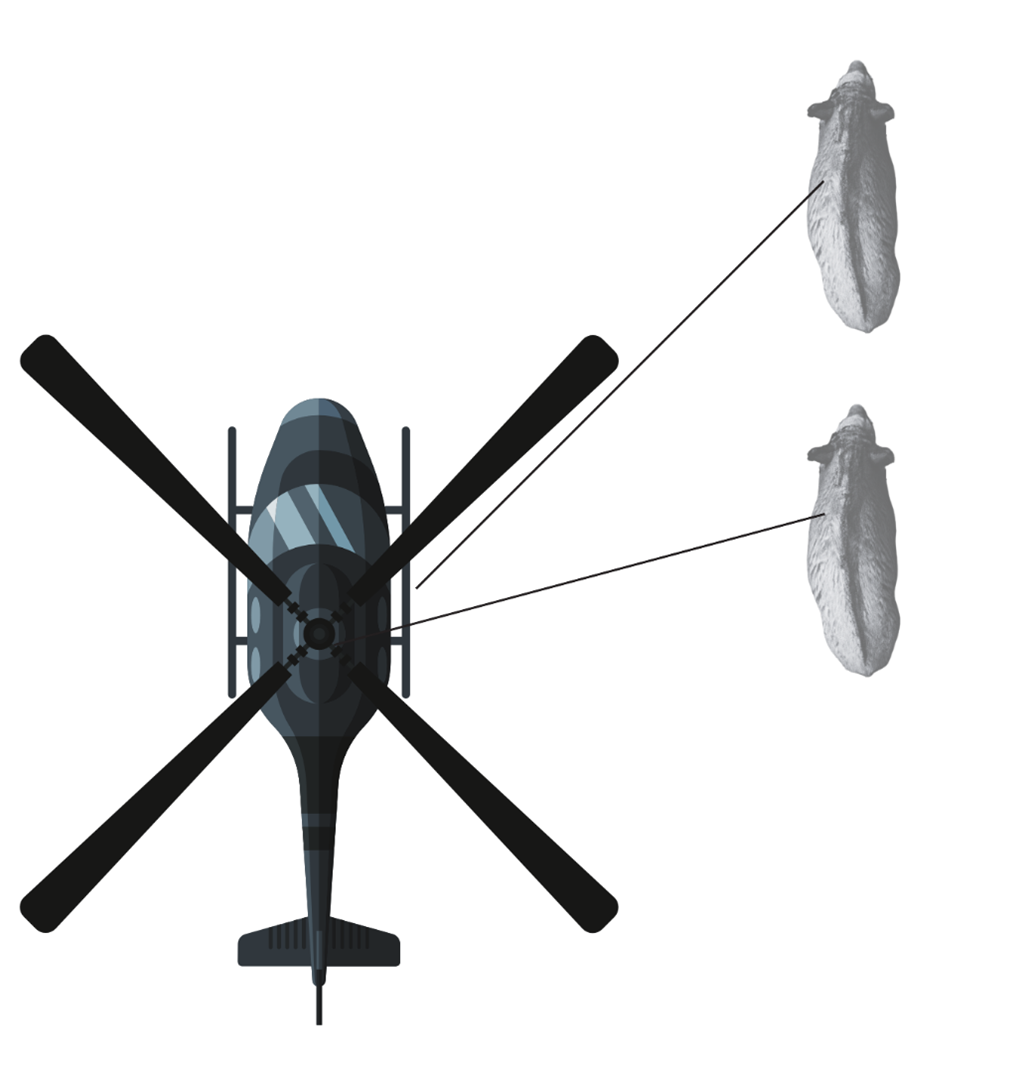

- The pilot should offer the shooter the best opportunities for a humane This includes maintaining a stable shooting platform and to ensure that the helicopter is always aligned so that the shooter can maintain accuracy and to avoid shots to unacceptable parts of the body e.g., spine or neck shots (Figure 3). Aerial shooting should not be carried out if the nature of the terrain or environmental conditions reduces accuracy resulting in inaccurate shooting and prevents the humane and prompt culling of wounded animals.

- If lactating sows are shot, reasonable efforts should be made to find dependent piglets and kill them quickly and Piglets older than 5 weeks of age will tend to fall in to line behind the sow. Any piglets that escape after a sow has been shot will usually return to the area over the following few hours.

- Aerial shooting programs by their nature must be highly accountable. Apart from maintaining absolute animal welfare standards, records should be kept of the number and location of animals killed, hours flown, ammunition used and fly-back procedures.

Non-target animals

- Shooting is relatively target specific and does not usually impact on other However, there is always a risk of injuring or killing non-target animals, including livestock, if shots are taken before an animal has been positively identified.

- Sensitive livestock such as horses, farmed deer and free-range poultry are easily frightened by gunshots, helicopter rotor noise, wind and may injure themselves by running into fences and other obstacles. Avoid shooting in areas where these livestock occur or organise the removal of them from the area prior to the shooting program.

Workplace health and safety considerations

- The potentially hazardous nature of aerial shooting requires that safety protocols be strictly followed. Each team member must be aware of and trained in all aspects of helicopter and firearm safety.

- The helicopter pilot must perform a thorough pre-flight briefing with all personnel to establish communication protocols between the shooter and the pilot including pre-shot manoeuvre, commands for firing and emergency procedures.

- Shooting from a helicopter can be hazardous, particularly in areas of rugged The combination of low-level flight, close proximity to obstacles (trees, rocks, and wires) and the use of firearms makes this task extremely hazardous.

- It is essential that ejected ammunition cases do not interfere with the safe operations of the helicopter. It might be necessary to fit a deflector plate or shell-catcher, to the firearm to ensure shells are ejected safely.

- Firearm users must strictly observe all relevant safety guidelines relating to firearm ownership, possession and use.

- When not in use, firearms must be securely stored in a compartment that meets state legal requirements. Ammunition must be stored in a locked container separate from firearms.

- Adequate hearing protection should be worn by the shooter and others in the immediate vicinity of the Repeated exposure to firearm noise can cause irreversible hearing damage.

- Safety glasses are recommended to protect the eyes from gases, metal fragments and other particles.

- Consideration should be given for personnel involved to be vaccinated for diseases such as Q-fever and Japanese encephalitis (JEV).

Equipment required

Firearms and ammunition

- Firearms should be:

- Reliable, well maintained and capable of good accuracy

- Fitted with an appropriate sight for operation at close range

- Rifles should be semi-automatic and of appropriate calibre e.g. .308 calibre and adequate magazine capacity.

- Shotguns should be 12-gauge and either pump action or semi- automatic, being fitted with the appropriate choke and having an adequate magazine capacity – for use on small to medium sized pigs only.

- Shooters must check ballistic charts for the specifications for the combination of firearm and ammunition they want to use.

- To provide a backup in case of firearm/ammunition malfunction, at least two functioning firearms should be carried by shooters at all times.

- The accuracy and precision of firearms should be tested against inanimate targets before any shooting operation.

- Ensure the firearm is sighted correctly for the expected operational distance.

- ‘Energy at the target’ and bullet construction are the most important factors when selecting firearms and ammunition to achieve humane shooting of animals. These requirements vary for different species, and size classes within species, depending on body size and composition.

- Ammunition

- Hollow point, 130gn -135gn; protected point 130gn or SG, SSG (larger pigs) and AAA, BB (small pigs or piglets)

- Examples of acceptable firearm and ammunition combinations for rifles with maximum shooting distances are included in the table below:

| Cartridge |

Bullet weight (gr) |

Muzzle velocity (ft/sec) |

Muzzle energy (ft-lbs) |

Maximum distance(metres)* |

| .308 Winchester |

130 |

3050 |

2685 |

70 |

| .308 Winchester |

135 |

3000 |

2699 |

70 |

Source:

https://www.federalpremium.com/rifle/american-eagle/american-eagle-varmint-and-predator/11-AE308130VP.html

https://www.osaaustralia.com.au/products/ammunition/centrefire-rifle/308-win/osa-ammo-308win-135gr-sierra-20-pack/

*With aerial shooting, most shots are taken at 20 to 50 metres and the maximum range would be about 70 metres

- Specifying ammunition based on species alone rather than individual body mass is problematic. Shooters should select ammunition (from those specified) that best suits their situation, and which is justifiable on animal welfare This may particularly apply to situations where multiple species are being controlled in the one operation.

- When using a shotgun, the pig should be no more than 20 metres from the shooter. The pattern of shot should be centred on the head or chest. It is essential that the distance to the target animal is accurately judged. To achieve adequate penetration of shot, the animal must be in range.

Aircraft

- Aircraft used for aerial shooting should be manoeuvrable, fast and responsive, being suitable to the task at hand and operating environment allowing for quick follow-up if any animals are wounded.

- GPS (global positioning systems) and computer mapping equipment with appropriate software should be used to assist in the accurate recording of information (e.g., where animals are shot) and to eliminate the risk of shooting in off-target areas.

Other equipment

- Flight helmet (with intercom).

- Fire-resistant clothing or flight suit.

- Safety harness.

- Other personal protective equipment including lace-up boots, gloves and appropriate eye and hearing protection.

- Survival kit (including a first aid kit.)

- Emergency locating beacon.

- Thermal binoculars or monocular (where applicable).

- Lockable firearm box.

- Lockable ammunition box.

Procedures

- Shooters must not shoot at an animal unless they are confident of cleanly killing it without unnecessary pain, distress or Only chest (heart-lung) or head (brain) shots must be used. Shooting at other parts of the body is unacceptable.

- Wounded animals can suffer from pain and the disabling effects of the injury (including sickness due to infection). The cost of ammunition and extra flying time must not deter operators from applying fly-back procedures.

- Where target animals are encountered in a group they should typically be shot from the back of the group first (the last one shot is furthest away from the helicopter). This may not always be possible e.g., when an animal breaks away from a group. In this case, the shooter and pilot need to communicate so they focus on the same animal.

- Each animal must be shot at least twice with at least one bullet placed in the heart/lung and before shooting further animals. The only exemption to two shots is when the heart/lung is completely destroyed after the first shot as may be the case with smaller animals.

- The shooter must shoot an animal more than twice in the following circumstances:

- where directed by the pilot or if the shooter considers it necessary

- until a bullet is placed in the heart/lung of the animal

- if the animal doesn’t appear dead (signs of life could include attempting to lift its head, any coordinated body movement, eye blinking or breathing).

- Each animal shot must be considered dead by the shooter and pilot, and verbally announced as a ‘kill’ by the pilot before shooting further animals. This procedure allows for both the shooter and pilot to make a judgement of each animal shot being dead, by the animal exhibiting no sign of life and/or by observing the placement of a bullet into the heart/lung.

- A fly-back procedure is required after shooting a group of animals and must be applied at all times. The procedure is as follows:

- fly-back over each animal of the group shot

- hover over each animal long enough to assess that the animal doesn’t exhibit any sign of life

- where there is any doubt by the shooter or pilot that the animal is dead or that there is a bullet in the heart/lung, the shooter is to shoot further bullet/s into the heart/lung of the animal.

- When large groups of animals are encountered or when groups are encountered in heavy vegetation, the shooter and pilot must consider the ability to conduct an effective fly-back procedure. If an effective flyback is likely to be hampered by continuing to shoot further animals in a group or when animals already shot are unlikely to be found, shooting should temporarily cease, and a fly-back conducted over animals already shot. This is not required when conducting thermal assisted aerial shooting due to different operational procedures compared with conventional aerial shooting.

- The best time to shoot feral pigs is when they are most active and away from cover; that is, in the early morning, late afternoon and During winter months and on cooler, overcast days pigs will be more active during daylight hours.

- Target pigs should be mustered away from watercourses and areas of dense vegetation before being shot, as wounded animals will be difficult to locate if they go down in these This also assists with optimising efficacy of aerial shooting activities.

- Once a target is sighted and has been positively identified, the pilot should position the helicopter as close as is safe to the target animal to permit the shooter the best opportunity for a humane kill.

- The pilot should aim to provide a shooting platform that is as stable as possible.

Target and shot placement

Although pigs are comparatively large animals, the vital areas targeted for clean killing are small. Shooters should be adequately skilled e.g. be able to consistently shoot (using at least the minimum specified centrefire rifle) a group of 3 shots (from 3 attempts) within a 7.5cm target at 100 metres using a bench rest. Shooters should also be able to accurately judge distance, wind direction and speed and have a thorough knowledge of the firearm and ammunition being used.

Head Shots

Poll position (rear view)

- When aerial shooting, most head shots will be taken at this position as animals are running away from the helicopter. The firearm should be aimed at the back of the head at a point between the base of the ears and directed towards the mouth.

Temporal position (side view)

- This shot is occasionally used where a second shot needs to be delivered to an injured animal that is lying on its The pig is shot from the side so that the bullet enters the skull at a point midway between the eye and the base of the ear.

Frontal position (front view)

- This position is occasionally used when an animal faces the The firearm is aimed at a point in the middle of the forehead slightly above a line drawn between the eyes.

Chest Shot

Side view

- The firearm is aimed at the centre of a line encircling the minimum girth of the animal’s chest, immediately behind the forelegs. The shot should be taken slightly to the rear of the shoulder blade (scapula). This angle is taken because the scapula and humerus provide partial protection of the heart from a direct side-on shot.

Figure 1: Shot placement for aerial shooting of feral pigs

Note that shooting an animal from above or below the horizontal level as depicted here will influence the direction of the bullet through the body. Adjustment to the point of aim on the external surface of the body may need to be made to ensure that the angled bullet path causes extensive (and therefore fatal) damage to the main organs in the target areas.

Figure 2: Shot placement for aerial shooting of feral pigs – aerial view

Figure 3: Shot placement for aerial shooting of feral pigs – aerial view illustrating the changing point of aim of a heart-lung shot with different aircraft to animal orientation

References

-

- Aebischer NJ, Wheatley CJ and Rose HR (2014) Factors associated with shooting accuracy and wounding rate of four managed wild deer species in the UK, based on anonymous field records from deer stalkers. PLoS One 9, e109698.

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) (2020) AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2020 edition. American Veterinary Medical Association. Available at: https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/2020-Euthanasia-Final-1-17-20.pdf

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) (2016) AVMA Guidelines for the Humane Slaughter of Animals Edition.

- Bengsen A, Gentle M, Mitchell J, Pearson H and Saunders GR (2014) Management and impacts of feral pigs in Australia. Mammal Review 44, 135-47.

- Choquenot D, McIlroy J and Korn T (1996) Managing vertebrate pests: pigs. Bureau of Resource Sciences. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

- Gregory N (2004) Physiology and behaviour of animal suffering. Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

- Longair J et al (1991) Guidelines for euthanasia of domestic animals by firearms. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 32, 724-726.

- Office of Environment and Heritage (2019 Draft) NSW Feral Animal Aerial Shooting Team (FAAST) Manual. OEH Sydney.

- Saunders GR (1993) Observations on the use of helicopters for feral pig control in western NSW. Wildlife Research 20, 771-776.

- Smith G (1999) A Guide to Hunting & Shooting in Australia. Regency Publishing, South Australia.

- Standing Committee on Agriculture and Resource Management Council. Feral Livestock Animals. Destruction or capture, handling and marketing. SCA Technical Report Series No. 34. CSIRO Publishing, Australia. Available at: https://www.publish.csiro.au/ebook/download/pdf/370

- Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (1976) Humane Destruction of Unwanted Animals. UFAW, Potters Bar, England.

- Woods J, Shearer JK and Hill J (2010) Recommended On-farm Euthanasia Practices. In ‘Improving Animal Welfare: A Practical Approach’. (Grandin T, Ed). CABI, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK.

The Centre for Invasive Species Solutions manages these documents on behalf of the Environment and Invasives Committee (EIC). The authors of these documents have taken care to validate the accuracy of the information at the time of writing. This information has been prepared with care but it is provided “as is”, without warranty of any kind, to the extent permitted by law.

Connect with government

It is important to contact the relevant federal, state or territory government agency before undertaking feral pig control to ensure you have the right permits in place.

Connect

FURTHER INFORMATION

Aerial shooting from helicopters is useful for rapid population reduction in large, inaccessible areas. Where pig densities are high, aerial shooting can kill many pigs at a time, quickly knocking down pig numbers in the short term. Aerial shooting is also useful when pigs show avoidance behaviour to baits, traps, vehicles and/or people on foot. Pigs can modify their behaviour if aerial shooting exercises are extended, making their detection harder.

Aerial shooting works best in open terrain or remote/ inaccessible areas, such as swamps, marshes or seasonally inundated areas. Such areas tend to have reasonable numbers of pigs and are open enough for the operator to see pigs from the air. Aerial shooting can be the only viable option in some areas where vehicle access is limited, or environmental conditions, such as widespread rainfall, severely limit the effectiveness of other ground-based control methods.

Aerial shooting is best carried out when pigs are most active (in the early morning or late afternoon, even during daylight hours in winter on cooler, overcast days) and when they are away from cover (during dry seasons or droughts). To maximise the effectiveness, timing for shooting should be balanced between winter (when pigs are more active than usual in daylight) and summer (when pigs concentrate around water points and light cover) although this will depend on local conditions.

Successful aerial shooting requires proficient marksmen, spotters and pilots. There are inherent safety risks associated with operating any aircraft at low attitudes above ground level. In some States (e.g. NSW) a qualified, trained marksman is required to be on board even when operating above private properties. In this case, it is important to consult with the landholders before the operation to confirm their property boundaries and hotspots to target. Hotspots can be identified by the landholders one or two days before the operation by looking for fresh pig tracks or diggings. Using aerial images of the property can be an effective way to discuss the hotspots. As a regulatory requirement, helicopter operators must have approval from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and shooters need to be accredited for competency. In NSW, they must complete the Feral Animal Aerial Shooter Training (FAAST) course.

To maximise kill rates, pigs should always be shot from the tail end of the mob first and move forward until the line has been shot. The most suitable weapons in aerial shooting include automatic shotguns or semi- automatic large calibre (.308) rifles. ‘Judas’ pigs may be useful in locating groups of pigs although previous results have been highly variable. Judas pigs are radio- collared individuals released to associate and reveal the location of pigs in an area that are difficult to find by other methods. They are used mostly for removing remaining pigs in the last stages of eradication campaigns. It is not effective to use Judas pigs when pig densities are high.